Tales of water told in art

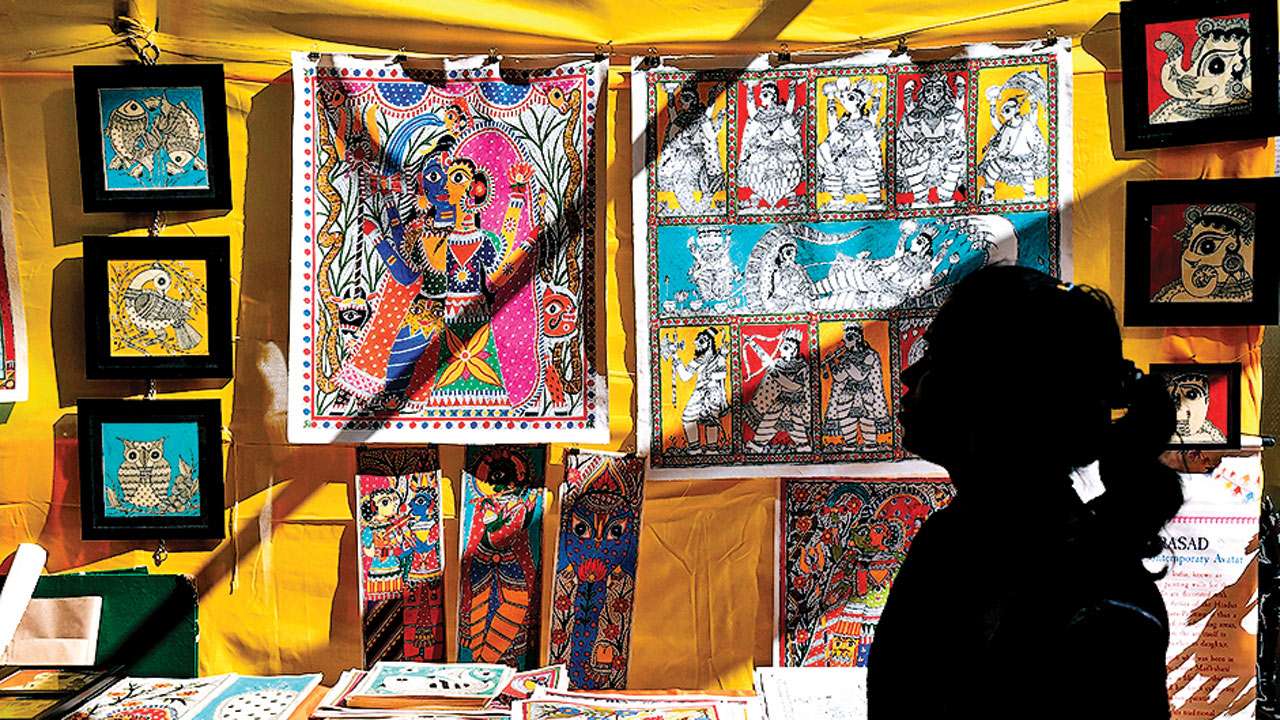

A visitor looks at the artwork at Madhubani art at the exhibition - Salman Ansari, DNA

Dotted fish swim across a bandhni dupatta, aquatic plants grace block-printed stoles, aquamarine gems glint in the sunlight and brighten the colourful cluster of India cork handicrafts. The third edition of Annual Handmade Collective by A Hundred Hands at the Bhau Daji Lad Museum (ongoing till January 14) followed the theme is water. Where preachy talks and didactic monologue may fail, some of the artists and artisans participating the exhibit have shown both through the use of motifs and the way in which they have cut down on water usage in their work.

Shubham Chhipa of Gopal Handprints, who hails from Jaipur, says that conserving water is even more important to him than achieving the perfect white in his handblock prints. “We recycle the water we use to wash the clothes after they have been dyed,” he explains. “Usually, the same dye is used twice a week and we keep the water aside to use for both washes along with leftover dye.”

Hailing from the outskirts of Bhuj, Sulaiman Khatri has also taken to using dyes that set easily as opposed to ones that require more washes for his bandhini brand Ababil. In Bengal, Rubi and Arup Rakshit of MG Gramodyog Sewa Sansthan, supply their muslin and jamdani weavers with rain-fed, short staple desi cotton instead of the water and fertiliser-intensive BT cotton. “Cloth from the latter has traces of chemicals, even after many washes. Desi cotton requires less water during the weaving process,” explains Arup.

(Shubham Chhipa of Gopal Hand Prints; Preeti from Aranya Earthcrafts; sholapith artist Gobindo Haldar)

(Shubham Chhipa of Gopal Hand Prints; Preeti from Aranya Earthcrafts; sholapith artist Gobindo Haldar)

While Khatri, Chhipa and Arup work with cloth, Preeti, who helms Aaranya Earthcrafts works with papier mache. A green pendant holds bronze lotus flowers and leaves, another in deep aquamarine looks like a lotus stem dotted with tiny bronze mushrooms. As her inspiration comes from nature, it was easy for her to rustle up artefacts on the theme of water. “We use the same water for soaking the paper, then the gond and then the mitti, as opposed to throwing it away each time,” explains the artist. “This takes more time, but the sequence of paper-gond-mitti remains the same.”

With just a bit of improvisation, the artistes show that saving water is not just possible but easy.

A Symbiotic Art

One of the more colourful shops at the exhibition is Gobindo Haldar’s sholapith shop. Hailing from a village on the outskirts of Kolkata, Haldar’s one of the few remaining exponents of art to use this spongey water plant growing in marshy land in Orissa, Assam and Bengal. Thanks to less intricate and more durable substitutes like plastic flowers and thermocole, Haldar finds his business endangered. “Once the wedding season used to see booming for shola artists since we supplied most of the decor. However, today, we struggle through the winter and wait for puja seasons,” laments Haldar, who has come to Mumbai with his colourful shola artwork with borrowed money and high hopes for buyers and wholesale tie-ups.